mirror of

https://github.com/mfocko/blog.git

synced 2025-05-03 18:02:59 +02:00

blog(lts-distros): add the finished post

Closes #14 Signed-off-by: Matej Focko <me@mfocko.xyz>

This commit is contained in:

parent

f2d3c4246e

commit

3f653f4bc8

1 changed files with 480 additions and 0 deletions

480

blog/2024-02-07-lts-distros.md

Normal file

480

blog/2024-02-07-lts-distros.md

Normal file

|

|

@ -0,0 +1,480 @@

|

||||||

|

---

|

||||||

|

title: LTS distributions

|

||||||

|

description: |

|

||||||

|

Shower thoughts on the LTS Linux distributions.

|

||||||

|

date: 2024-02-07

|

||||||

|

authors:

|

||||||

|

- key: mf

|

||||||

|

title: a.k.a. small Fedora maintainer

|

||||||

|

tags:

|

||||||

|

- lts

|

||||||

|

- linux distributions

|

||||||

|

- support

|

||||||

|

- paywall

|

||||||

|

hide_table_of_contents: false

|

||||||

|

---

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Linux distributions are a common choice for running the servers. There's a wide

|

||||||

|

variety of distributions, but on the servers majority is made by only a few.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Some corporations also profit from the support of the “big” distributions. Let's

|

||||||

|

dive into the pros, cons and peculiarities of such _business_.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

This post is inspired/triggered by the following Mastodon post:

|

||||||

|

[](https://hackers.town/@antijingoist/111864760073049505)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

<!--truncate-->

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

:::caution Disclaimer

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

You may take my opinion with a grain of salt, since I'm affiliated with Red Hat,

|

||||||

|

but at the same time I've also seen the other side of the fence, so I know how

|

||||||

|

it works from the perspective of the provider/maintainer.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

:::

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

:::tip

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

If you are not very oriented in the matters of Linux distributions and

|

||||||

|

maintaining of packages, I suggest looking at the [glossary](#glossary) at the

|

||||||

|

end to have a better grasp of the terms that are used throughout the post.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

:::

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Point of linux distributions

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

First thing I'd like to point out is the point of the Linux distributions. What

|

||||||

|

benefit do they provide? And why there are so many of them…

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

As it has been brought up many times by the _rms_[^1], Linux by itself is not

|

||||||

|

enough, it's just the kernel that does the underlying work. We need more

|

||||||

|

software to utilize the hardware. That's the gap that Linux distributions bridge

|

||||||

|

by providing the Linux and much more other software that we need.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Each distribution is unique in its own way. Some prefer different ways of

|

||||||

|

handling the software (like Gentoo that allows you to compile it yourself) and

|

||||||

|

others stable releases of software (like Debian).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

In the end it mostly boils down to the packaging. I, as a user, want to do

|

||||||

|

something like

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

```

|

||||||

|

$ sudo dnf5 install firefox

|

||||||

|

```

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

and not bother about anything else. I don't want to open browser to look the

|

||||||

|

thing up, download it and then click mindlessly 500× “Next”. I just want to run

|

||||||

|

one command and when the maintainers decide it's time to move on, another one to

|

||||||

|

upgrade the software to the newer version.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Of course, for some use cases you want to minimize the latter. And even make

|

||||||

|

sure that it's safe to do it when you need to. You don't want to break your

|

||||||

|

production deployment just because someone decided it's time to push something

|

||||||

|

out.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

That's when the _maintainers_ come in. They take upon themselves the

|

||||||

|

responsibility of maintaining the packages. If you've ever used the Debian, you

|

||||||

|

know very well how _old_ the software is, but that's what you might need for

|

||||||

|

your servers.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Pain of packaging

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Packaging software _is not_ cost-free. You may as well have 80 % of packages

|

||||||

|

that don't need much care and it's rather easy to push them forward, but those

|

||||||

|

remaining, which are complicated and raise issues regularly, will make it up and

|

||||||

|

take a lot of time and also pain.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Libraries are the most common example that might not need much work to be done.

|

||||||

|

On the other hand, Linux kernel itself is a rather complicated machinery that

|

||||||

|

is patched **a lot** and its build process is not simple either.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Even if you consider just those _easily-maintainble_ packages, the process can

|

||||||

|

be tedious, boring and overall time consuming.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

:::tip Shameless RHEL-based ecosystem plug

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

[Packit] can help tremendously with the _easily-maintainable_ packages, since it

|

||||||

|

**can** be automated.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

:::

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Packaging whole ecosystems

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Now it's time to talk about whole ecosystems that have some kind of a packaging

|

||||||

|

by themselves. Yes, I mean Python (with its continuous stream of different

|

||||||

|

package managers), Rust, Go, etc.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Whole point of packaging is to have some form of _gating_. In other words, you

|

||||||

|

want some kind of _quality control_ when pushing changes into the Linux distros.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

If you want to package some tool (or even library) from the aforementioned

|

||||||

|

ecosystems, you need to package all of the dependencies to make sure something

|

||||||

|

doesn't get updated in the meantime (and also that you can safely reproduce the

|

||||||

|

builds, if need be).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

I've tried to package some utilities for EPEL both in Rust and Go. Dependencies

|

||||||

|

form a DAG[^2] and in case of Rust, it's _very_ similar to the way `npm` does

|

||||||

|

its packaging.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

:::danger Spoiler alert

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

You get a lot of dependencies. And since it's a tree of dependencies, there may

|

||||||

|

be **a lot** of them.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

:::

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

I have no clue how do the Rust maintainers operate, but I'm tipping my fedora in

|

||||||

|

their direction, since it must be a _pain in the ass_.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Paid distributions

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

You can find few Linux distributions that are “paid”. I'm very well aware of the

|

||||||

|

fact I've used quotes around the word, cause it's not that easy and not even

|

||||||

|

same for all of the distributions that involve some kind of a payment.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

One of the first non-free distributions I've come into contact was _[Zorin OS]_

|

||||||

|

which basically tries to be the best _transition_ solution when moving away from

|

||||||

|

the Windows or macOS. If you have a look at the _perks_ of its _Pro_ version

|

||||||

|

that's paid, you may as well decide they are rather questionable…

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

It's time to move into the _Ubuntu Pro_, _RHEL_ and _SLE_ territory. What's the

|

||||||

|

point of those? They definitely offer different kind of, let's say,

|

||||||

|

_non-free experience_.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

With those you are paying mainly for the support and bug/security patches.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

:::tip Fun fact

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

There's no mention of any kind of support on the Zorin page… Apart from the fact

|

||||||

|

that _you are supporting_ the Zorin development.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

:::

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Repository structure

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

As I have mentioned above, the three _services_[^3] I mentioned are providing

|

||||||

|

support with regards to bugs and security vulnerabilites. Therefore it makes

|

||||||

|

sense to have some kind of a process in place when you're pushing changes

|

||||||

|

(either updates, patches or _security_ patches) to the distribution. And yes,

|

||||||

|

these processes are _in place_.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

If you think about the amount of packages that is present in the community

|

||||||

|

distributions like _archLinux_ (14,830 packages) or _Fedora_ (74,309 packages),

|

||||||

|

it is safe to come to a conclusion that _there's no way_ to support all of them.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

:::tip archLinux

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

It may seem that archLinux contains rather small set of packages, but one of the

|

||||||

|

_killer features_ of archLinux lies in the AUR (archLinux User Repository) where

|

||||||

|

you can find additional **93,283** packages.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

:::

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

That's why the Linux distributions have some structure to their repositories

|

||||||

|

that contain packages. The way you go around this is rather simple, you choose

|

||||||

|

some set of _critical_ packages that you guarantee support for (like Linux

|

||||||

|

kernel, openSSL, etc.) and maintain those with all the QA processes in place.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

:::caution Unpopular opinion

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

This is also one of the reasons why I'm quite against packaging anything and

|

||||||

|

everything into the Linux distribution. In my opinion it is impossible to

|

||||||

|

**properly** maintain **huge** set of packages and enforce some kind of

|

||||||

|

**quality control**.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

:::

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Ubuntu

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Ubuntu has pretty granular structure of their repositories, namely:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- `main` containing the “core” of the Ubuntu that is maintained by the Canonical,

|

||||||

|

- `universe` containing literally the “universe”, packages that everyone likes,

|

||||||

|

but they're not crucial, this repo is maintained mostly by the community,

|

||||||

|

- `multiverse` containing packages with some license or copyright issues, and

|

||||||

|

- `restricted` containing _proprietary_ packages like nvidia drivers and such.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

By briefly checking my Ubuntu 23.10 installation, here are stats of packages in

|

||||||

|

their respective repositories:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- `main` with 6,128 packages,

|

||||||

|

- `universe` with 63,380 packages,

|

||||||

|

- `multiverse` with 997 packages, and finally

|

||||||

|

- `restricted` with 784 packages.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

As you can see, if we sum them up, they are relatively similar to the Fedora

|

||||||

|

numbers.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### CentOS

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

CentOS on the other hand has a bit simpler structure with BaseOS for the base

|

||||||

|

and AppStream for additional packages:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- `baseos` with 1,058 packages,

|

||||||

|

- `appstream` with 5,646 packages, and

|

||||||

|

- `extras-common` with 42 packages.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Overall they make up the similar number as the Ubuntu's `main` repository. And

|

||||||

|

you can also notice that there are no additional repositories.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

:::tip

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

There's also a CRB (CodeReady Builder) repository with dev packages like headers

|

||||||

|

and such.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

And you can also enable EPEL (Extra Packages for Enterprise Linux) which is

|

||||||

|

community-supported and provides another 19,903 packages.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

:::

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Ubuntu Pro

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Now it's time to get back to the Ubuntu Pro. There are multiple points that need

|

||||||

|

to be taken in account to be either positive or negative about it…

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

We can start with the way Ubuntu is released and maintained. Ubuntu has regular

|

||||||

|

6-month release cycle and biannual LTS release. Releases are normally supported

|

||||||

|

for 9 months with the exception of the LTS releases being supported for 5 years.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

If you check out the _[Ubuntu Pro]_ website, you can find the following

|

||||||

|

statement:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> **Ubuntu Pro**

|

||||||

|

>

|

||||||

|

> The most comprehensive subscription for open-source software security

|

||||||

|

>

|

||||||

|

> 30-day trial for enterprises. Always free for personal use.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

:::tip Personal use

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Ubuntu Pro for _personal use_ consists of 5 installations and in case of the

|

||||||

|

community _ambassadors_ 50.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

:::

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Overall if you try to find what is included in the Ubuntu Pro:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- high and critical patches,

|

||||||

|

- 10 years of maintenance, and

|

||||||

|

- (optional) 24/7 enterprise-grade support.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

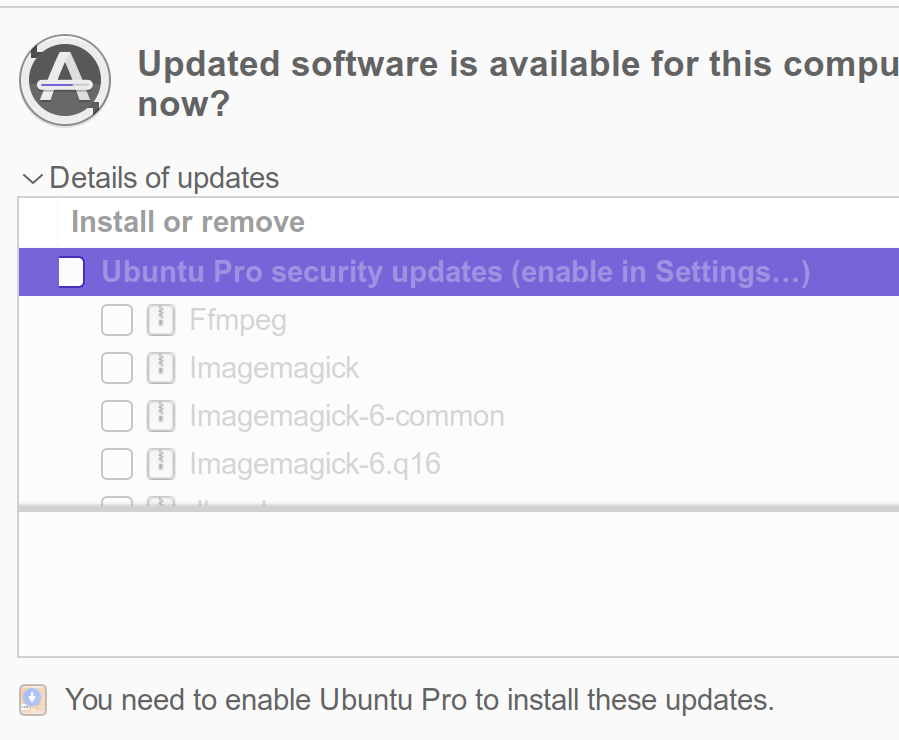

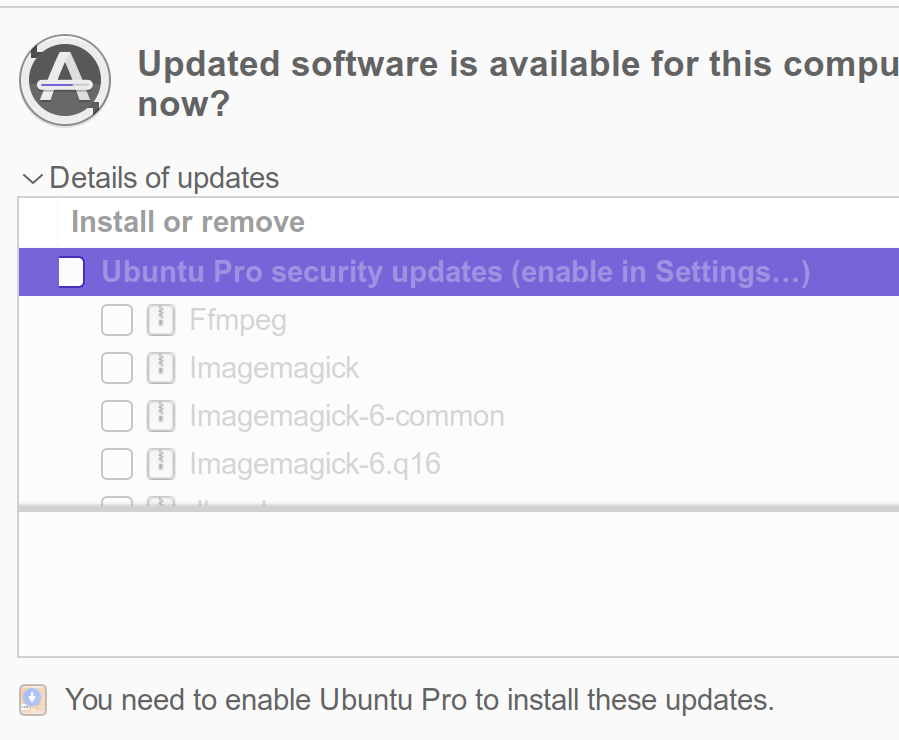

If we get back to the screenshot all the way at the beginning of the post:

|

||||||

|

[](https://hackers.town/@antijingoist/111864760073049505)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

and try to look up to which repository the packages mentioned in the screenshot

|

||||||

|

belong, we will find out that they belong to `universe` repository which is

|

||||||

|

maintained by the community. Not to mention nature of the packages: multimedia.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

You may think about this as a scam, but considering repository consisting of 70k

|

||||||

|

packages, it is not an easy task to do. And with LTS releases we're talking

|

||||||

|

about 5+ years of support.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

:::info Fedora

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Try to compare this state to Fedora. It also has a 6-month release cycle, but

|

||||||

|

there are no LTS releases and each release is supported only for a year.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

:::

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Common strategy, at this point, is to pull out the _open-source_. Yes, we are

|

||||||

|

still dealing with the open-source, but keep in mind that you're trying to patch

|

||||||

|

some issue in a version that's 5 years old, upstream definitely doesn't care

|

||||||

|

anymore[^4], the development didn't stop 5 years ago, it's going on and fixing

|

||||||

|

this issue in a release from 5 years is not the same as fixing it in the current

|

||||||

|

release. At this point, if you are paying for such support, you are actually

|

||||||

|

paying for someone to do _software archaeology_ which **can be** _non-trivial_

|

||||||

|

to do.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

In the case of Ubuntu Pro we're talking about community support and best-effort

|

||||||

|

support by Canonical for the paying customers. And that makes sense to me,

|

||||||

|

running LTS distro for 5+ years on a desktop seems like an odd choice, even

|

||||||

|

with the help of _[podman]_ and _[distrobox]_ or _[toolbx]_ that allow us to use

|

||||||

|

stable or LTS distro as a base and containerized development environments on top

|

||||||

|

of that.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## RHEL ecosystem

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

RHEL ecosystem is much more complicated in this matter. However it's very

|

||||||

|

similar to the way SUSE operates with few exceptions.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

You can see a flow diagram here:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

```mermaid

|

||||||

|

flowchart LR;

|

||||||

|

U[upstream] --> FR[Fedora Rawhide];

|

||||||

|

FR --> F[Fedora release];

|

||||||

|

F --> C[CentOS Stream];

|

||||||

|

C --> R[RHEL];

|

||||||

|

```

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Key things to take and not to take from the flow diagram:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- getting from one upstream to its respective downstream is not as simple as the

|

||||||

|

presence of an arrow and it's not the same process for all of them

|

||||||

|

- lengths of the arrows are not proportional, specifically:

|

||||||

|

- Fedora Rawhide is _supposed to_ consume updates as soon as possible,

|

||||||

|

- depending on the decision of the maintainer they can, but _don't have to_ be

|

||||||

|

included in the currently supported Fedora releases (you can take [Emacs] as

|

||||||

|

an example of such package), but Rawhide eventually becomes the next Fedora

|

||||||

|

release,

|

||||||

|

- CentOS Stream gets branched off a specific Fedora release, and then

|

||||||

|

- ultimately CentOS Stream becomes the next **minor** release of RHEL.

|

||||||

|

- this diagram is simplified by **a lot**

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

:::tip SUSE flow for comparison

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

I'll also include a SUSE flow, so you can compare:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

```mermaid

|

||||||

|

flowchart LR;

|

||||||

|

U[upstream] --> T[openSUSE Tumbleweed];

|

||||||

|

T --> L[openSUSE Leap];

|

||||||

|

L --> S[SUSE Linux Enterprise];

|

||||||

|

S --> L;

|

||||||

|

```

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

You can notice, as opposed to the RHEL ecosystem, some changes are being

|

||||||

|

backported to the openSUSE Leap.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

However this is subject to change as there is a new [ALP] project arising which

|

||||||

|

is, more than likely, going to replace the Leap.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

:::

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Change in the model

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

The flow I've shown above is in effect since late ‘20 and early ‘21. I hope you

|

||||||

|

can see that it is quite similar to the way SUSE operates too. Before late ‘20

|

||||||

|

the flow was following:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

```mermaid

|

||||||

|

flowchart LR;

|

||||||

|

U[upstream] --> FR[Fedora Rawhide];

|

||||||

|

FR --> F[Fedora release];

|

||||||

|

F --> R[RHEL];

|

||||||

|

R --- C[CentOS];

|

||||||

|

```

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

CentOS was the last distribution in that “chain”. This provides some benefits

|

||||||

|

and some negatives.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Before the change

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

From the point of a developer, unless you have some kind of an early access to

|

||||||

|

RHEL, you don't see the changes until they land and are already released. This

|

||||||

|

impairs your ability to test and verify your software before shipping it to your

|

||||||

|

clients that use RHEL.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

From the point of a user, there is one positive, you basically get “free RHEL”

|

||||||

|

without the support. This also allowed you to report bugs against the RHEL,

|

||||||

|

since they were 1:1 distros (minus the branding and support). So you'd

|

||||||

|

technically get RHEL free of charge.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Benefit of such project, except for the cost, is questionable. The main issue,

|

||||||

|

which actually became even more apparent after changing the flow, is someone

|

||||||

|

else repackaging your own product and selling it again.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### After the change

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

First of all, the current flow counters the issue mentioned above. You can test

|

||||||

|

your projects against the _next minor RHEL release_. CentOS Stream is free, so

|

||||||

|

you can freely incorporate it into your CI pipelines.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

:::tip Shameless plug pt. 2

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Again, [Packit] can help you on upstream to verify that you're not breaking your

|

||||||

|

RPM builds and on top of that you can also use [Testing Farm] to run tests on a

|

||||||

|

specific Fedora or CentOS Stream releases.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

> Green tests may not be green everywhere and catching such issues as soon as

|

||||||

|

> possible costs much less than catching them further down the chain.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

:::

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

There are many people thinking that RHEL has become closed-source. It is not.

|

||||||

|

The development happens _out in the open_, it's more open that it was before.

|

||||||

|

However with the cost of not getting the exact same thing for free. You can get

|

||||||

|

the next minor RHEL, not the same that's normally paid for. [Packit] is an

|

||||||

|

example of a service that is deployed on the CentOS 9 Stream and even used to be

|

||||||

|

deployed on Fedora, but the regular 6-month release cycle caused some minor

|

||||||

|

issues here and there.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

_Production-ready_ is something that heavily depends on the context…

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

:::tip Free “clones”

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

After this change so-called _free “clones”_ emerged. I have to admit that in

|

||||||

|

case of _[AlmaLinux]_ I can see some benefits e.g., pushing for live images and

|

||||||

|

support of various desktop environments, Raspberry Pi support or even WSL images

|

||||||

|

being present in the M$ Store and easy to install.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

:::

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Open-source and paid support

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Overall I don't think that paying for the support of 5 years old _non-critical_

|

||||||

|

packages is going against the open-source. It is a non-trivial work that, in

|

||||||

|

majority of cases, cannot be included in the upstream, therefore the benefit is

|

||||||

|

reapt only by the paying customers. I have to admit that in the case of the

|

||||||

|

Ubuntu Pro it may seem a bit weird (hiding patches behind the paywall). However

|

||||||

|

we're still talking about rather big set of packages that will affect a minority

|

||||||

|

of server workloads, if any.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Glossary

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- _rolling release_ - continuously released without “significant milestones”

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

:::tip

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

As an example of rolling distribution you can take archLinux, openSUSE

|

||||||

|

Tumbleweed, Fedora Rawhide, or even CentOS 9 Stream.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

As en example of **not** rolling distribution you can take Ubuntu, openSUSE

|

||||||

|

Leap or Fedora.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

:::

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- _bleeding edge_ - contains the latest versions as they are released on the

|

||||||

|

upstream

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

:::tip

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

As an example you can take archLinux, openSUSE Tumbleweed or Fedora Rawhide.

|

||||||

|

You can also notice how common it is to combine _rolling release_ with

|

||||||

|

_bleeding edge_.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

:::

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- _upstream_ & _downstream_

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

You're most likely to meet these terms in the meaning of upstream being the

|

||||||

|

project itself and downstream being the packaging of said project in some

|

||||||

|

distribution.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

However this can also apply to distributions like _openSUSE Tumbleweed_ with

|

||||||

|

_openSUSE Leap_, _Fedora_ with _CentOS Stream_, or even _CentOS Stream_ with

|

||||||

|

_RHEL_. This basically means that the packages/software is being released into

|

||||||

|

the upstream (Tumbleweed, Fedora, or even CentOS) and then after being tested

|

||||||

|

is taken further down into their respective downstreams (Leap, CentOS, RHEL).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

[almalinux]: https://almalinux.org/

|

||||||

|

[alp]: https://susealp.io/

|

||||||

|

[distrobox]: https://distrobox.it/

|

||||||

|

[emacs]: https://src.fedoraproject.org/rpms/emacs/

|

||||||

|

[packit]: https://packit.dev/

|

||||||

|

[podman]: https://podman.io/

|

||||||

|

[testing farm]: https://docs.testing-farm.io/Testing%20Farm/0.1/index.html

|

||||||

|

[toolbx]: https://containertoolbx.org/

|

||||||

|

[ubuntu pro]: https://ubuntu.com/pro/

|

||||||

|

[zorin os]: https://zorin.com/os/pro/

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

[^1]: Richard Stallman

|

||||||

|

[^2]: directed acyclic graph

|

||||||

|

[^3]:

|

||||||

|

Ubuntu Pro is technically a service whereas the RHEL and SLE are distros

|

||||||

|

with the support included.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

[^4]:

|

||||||

|

There are upstream projects that keep LTS branches, such as Linux kernel,

|

||||||

|

but even in the case of the kernel itself, they're planning on ending it,

|

||||||

|

since the cost outweighs the benefits at this point.

|

||||||

Loading…

Add table

Add a link

Reference in a new issue